MCMC for Gaussian Mixture Models

Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) are incredibly versatile tools for solving real-world problems, from clustering and image analysis to speech processing. They enable us to model complex, multimodal data distributions effectively. Traditionally, the Expectation-Maximization algorithm is used to estimate the parameters of these models.

But what happens if we shift to a Bayesian approach? In a Bayesian setting, we gain the advantage of incorporating prior knowledge and quantifying uncertainty, but this comes at the cost of more complex computations. In order to compute the quantities of interest, we turn to Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which allow us to sample from the posterior distribution of the model’s parameters.

Recently I implemented a completed a project on comparing different MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) samplers when estimating the parameters of Hierarchical Guassian Mixture Model, and thought I’d share some details! You can find the code of the project here. In a nutshell, it allows the user to test and compare the results from different samplers when estimating a Hierarchical Gaussian Mixture Model. The “workflow” is:

- Generate data from a Gaussian Mixture with known parameters (we do this for the different cases we are interested in: low/high overlap …)

- Use the Hierarchical Gaussian Mixture Model to estimate the parameters of the mixture which generated the data

- Compare the different samplers considered (in our case, NUTS, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, Metropolis-Hastings and Gibbs sampling) to determine which one gives the optimal results

The project was implemented using PyMC, which by default implements most samplers, but not Gibbs sampling. In this post, I’ll walk you through the theoretical derivation of the Gibbs Sampler for this model!

Note: In this case, for simplicity, we assumed that the weights \(\pi\) in the mixture are known. Though the model can be easily extended to include a Dirichlet prior on the probability vector \(\pi\).

1. Full conditional

The model we are interested in is

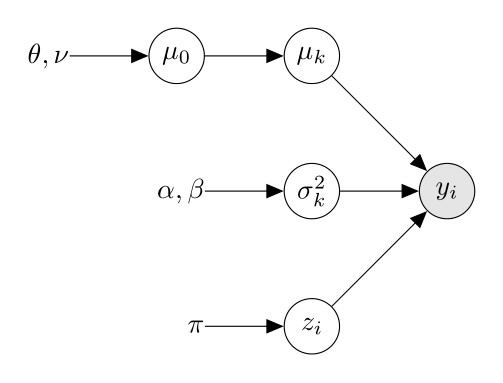

\[\begin{align*} & \mu_0 \sim \mathcal{N}(\theta, \nu) \\ & \mu_k | \mu_0 \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_0, \tau^2), \quad \text{$\tau^2$ known} \\ & \sigma^2_k \sim \text{InvGamma}(\alpha, \beta) \quad \text{$\alpha$, $\beta$ known} \\ & z_i \sim \text{Categorical}(\pi) \\ & y_i | z_i = k, \mu_k, \sigma_k^2 \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_k, \sigma^2_k) \end{align*}\]Note that we use the term hierarchical as we added a hyperprior \(\mu_0\), which the means of the components \(\mu_k\) depend on.

Which we can represent the model graphically as:

In order to use Gibbs sampling we have to obtain the conditional distribution of each of the components in the model. Using the graphical representation is helpful in obtaining the conditional distributions of the different components.

1.1 Conditional for \(z_i\)

We have

\[\text{p}(z_i | y_i, \mu_k, \sigma^2_k, \mu_0) = \text{p}(z_i | y_i) = \frac{\text{p}(y_i | z_i) \text{p}(z_i)}{\text{p}(y_i)} = \frac{\pi_k \mathcal{N}(\mu_k, \sigma^2_k)}{\sum_{j = 1}^k \pi_j \mathcal{N}(\mu_j, \sigma^2_j)}\]1.2 Conditional for \(\mu_k\)

We denote \(\mu_{-k} = (\mu_1, \mu_2, \dots, \mu_{k-1}, \mu_{k+1}, \dots, \mu_n)\) as the vector of means with the \(k\)-th element removed and \(N_i = \#\{i: z_i = 1\}\), the number of observations such that \(z_i = 1\).

\[\begin{align*} \text{p}(\mu_k | \mu_{-k}, z_i, \mu_0, \sigma^2_k, y_i) &= \text{p}(\mu_k | z_i, \mu_0, \sigma^2_k, y_i) \\ & \propto \prod_{i: z_i = k} \text{p}(y_i | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k, \mu_0) \text{p}(\mu_k, \mu_0, \sigma^2_k) \\ & \propto \text{p}(\mu_k | \mu_0) \prod_{i: z_i = k} \text{p}(y_i | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k) \\ & \propto \text{exp}\left\{\underbrace{-\frac{1}{2 \tau^2} (\mu_k - \mu_0)^2 + \sum_{i: z_i = k} \frac{1}{2 \sigma_k^2} (y_i - \mu_k)^2}_{(*)} \right\} \end{align*}\]We consider the expression in the last line inside the exponential, and expand it as

\[\begin{align*} (*) &= \frac{\sum_{i: z_i = k} y_i^2}{2 \sigma^2_k} + \frac{N_i \mu_k^2}{2 \sigma_k^2} - \frac{\mu_k \sum_{i: y_i = k} y_i}{2 \sigma^2_k} - \frac{1}{2 \tau^2} \mu_k^2 - \frac{1}{2 \tau^2} \mu_0^2 + \frac{2}{\tau^2}{\mu_k\mu_0} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \left\{ \underbrace{\left( \frac{N_i}{\sigma_k^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^2} \right)}_{a} \mu_k^2 - 2 \underbrace{\left( \frac{1}{\tau^2} \mu_0 + \frac{\sum_{i: z_i = k}y_i}{\sigma_k^2} \right)}_{b} \mu_k + \underbrace{\frac{\sum_{i: z_i = k} y_i^2}{\sigma_k^2} - \frac{1}{\tau^2} \mu_0^2}_{c} \right\} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \{a \mu_k^2 - 2b \mu_k + c\} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \left\{ a \left( \mu_k^2 - 2 \frac{b}{a} \mu_k \textcolor{red}{\pm \frac{b^2}{a^2}} \right) + c \right\} \\ &= - \frac{1}{2} \left\{ a \left( \left( \mu_k - \frac{b}{a}\right)^2 - \frac{b^2}{a^2} \right) + c \right\}. \end{align*}\]So, we conclude that

\[\boxed{\mu_k | \mu_{-k}, z_i, \mu_0, \sigma^2_k, y_i \sim \mathcal{N}\left( \frac{b}{a}, \frac{1}{a} \right).}\]This implies that

\[\begin{align*} & \mathbb{E}[\mu_k | \mu_{-k}, z_i, \mu_0, \sigma^2_k, y_i] = \frac{b}{a} = \frac{\frac{N_i}{\tau^2} + \frac{\sum_{i: z_i = k} y_i}{\sigma_k^2}}{\frac{N_i}{\sigma_k^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^2}} \\ & \text{Var}(\mu_k | \mu_{-k}, z_i, \mu_0, \sigma^2_k, y_i) = \frac{1}{a} = \frac{1}{\frac{N_i}{\sigma_k^2} + \frac{1}{\tau^2}}. \end{align*}\]The main “trick” needed to obtain the result is simply adding and subtracting \(\frac{b}{a}\). I’ve personally found this idea to be extremely useful in cases similar to this, where we need to manipulate algebraic expressions in order to obtain the distribution “we are looking for”.

1.3 Conditional for \(\mu_0\)

As for \(\mu_0\), we have

\[\begin{align*} \text{p}(\mu_0 | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k, y_i, z_i) &= \text{p}(\mu_0 | \mu_k) \\ &\propto \text{p}(\mu_k | \mu_0) \text{p}(\mu_0) \\ &\propto \text{exp}\left\{ -\frac{1}{2 \tau^2} \sum_{k = 1}^K (\mu_k - \mu_0)^2 - \frac{1}{2 \nu^2} (\mu_0 - \theta)^2 \right\}. \end{align*}\]Using an analogous process as that used for \(\mu_k\), we can write

\[\text{p}(\mu_k | \mu_0) \text{p}(\mu_0) \propto \text{exp}\left\{-\frac{1}{2} \left(a \mu_0^2 + b \mu_0 + c \right) \right\},\]where \(a = \frac{1}{\tau^2} + \frac{1}{\nu^2}\), \(b = \frac{\sum_{k = 1}^K \mu_k}{\tau^2} + \frac{\theta}{\nu^2}\) and \(c = \frac{\sum_{k = 1}^K \mu_k^2}{\tau} + \frac{\theta^2}{\nu^2}\).

Considering the expression inside the exponential, we can write

\[a \mu_0^2 + b \mu_0 + c = a\left( \mu_0^2 + \frac{b}{a}\mu_0 \textcolor{red}{\pm \frac{b^2}{a^2}} \right) + c = a \left( \left( \mu_0 - \frac{b}{a} \right)^2 - \frac{b^2}{a^2} \right) + c.\]Then, we have that

\[\boxed{\mu_0 | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k, y_i, z_i \sim \mathcal{N}\left(\frac{b}{a}, \frac{1}{a}\right).}\]So, in terms of expected value and variance we have

\[\begin{align*} & \mathbb{E}[\mu_0 | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k, y_i, z_i] = \frac{b}{a} = \frac{\frac{\sum_{k = 1}^K \mu_k}{\tau^2} + \frac{\theta}{\nu^2}}{\frac{1}{\tau^2} + \frac{1}{\nu^2}}, \\ & \text{Var}(\mu_0 | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k, y_i, z_i) = \frac{1}{a} = \frac{1}{\frac{1}{\tau^2} + \frac{1}{\nu^2}}. \end{align*}\]1.4 Conditional for \(\sigma_k^2\)

As \(\sigma_k^2 \sim \text{InvGamma}(\alpha, \beta)\) we can write its density as

\[f(\sigma_k^2; \alpha, \beta) = \frac{\beta^\alpha}{\Gamma(\alpha)} (\sigma_k^2)^{-(\alpha + 1)} \text{exp}\left\{- \frac{\beta}{\sigma_k^2} \right\}.\]We can write the condtional density as

\[\begin{align*} \text{p}(\sigma^2_k | \mu_k, \mu_0, y_i, z_i) &\propto \prod_{i: z_i = k} \text{p}(y_i | \mu_k, \sigma^2_k) \text{p}(\sigma_k^2) \\ &= (\sigma_k^2)^{-\left(\alpha_0 + 1 + \frac{N_k}{2} \right)} \text{exp} \left\{ - \frac{1}{\sigma_k^2} \left( \beta_0 + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i: z_i = k} (y_i - \mu_k)^2 \right) \right\} \end{align*}\]Letting \(\alpha' = \alpha_0 + \frac{N_k}{2}\) and \(\beta' = \beta_0 + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i: z_i = k} (y_i - \mu_k)^2\), we have

\[\boxed{\sigma^2_k | \mu_k, \mu_0, y_i, z_i \sim \text{InvGamma}(\alpha', \beta').}\]That’s it! We now have all the conditional distributions we need to implement the sampler. You can view the code here.

2. Some Thoughts

On PyMC

Implementing the Gibbs sampler with PyMC proved relatively straightforward when dealing with the univariate model. All that was required was implementing a custom class which inherited from the BlockedStep step method contained in the PyMC library. This allows us to implement a custom sampler and let PyMC do the heavy lifting in terms of providing convergence statistics, saving the results, plotting the estimated distributions etc…

When it came to implementing the sampler for the multivariate version of this model model (which extends the means \(\mu_k, \mu_0\) and uses a joint Normal-Inverse Wishart prior for \((\mu_k, \Sigma_k)\)), things started to break down. I still haven’t quite figured out why, but using PyMC resulted in degenerate situations in which all the observations are assigned to one component, the covariance matrix sampled is singular (even when using the advised prior and regularizing the terms), and other similar errors which made it extremely frustrating to work with PyMC. I’m still not quite sure whether these errors are due to the formulation of the model or some PyMC internals which I’m not too familiar with. Though frustrating it has been insightful in learning how PyMC works in more detail, though for the multivariate model I might turn to using a different framework or code the whole sampling process from scratch!

Mixture Models

While at first deriving all the full condtionals for these models can seem like a daunting task, once you have written down the graph representing the model most of the heavy lifting is done. At this point, all you really need to get your full conditionals are:

- Obviously, Bayes’ theorem!

- Dropping any terms which do not depend on the parameter of interest

- Using the two above, recognizing the kernel of known random variables to derive the actual full conditional distribution

- As in the case of \(\mu_0\) and \(\mu_k\), conveniently renaming some of the terms for ease of notation and, once we have an easier to interpret expression, using some good old algebra to try to obtain the expression we are looking for (in this case, completing the square and obtaining the Guassian kernel)

I would like to thank Dominique Paul for reading the first version of this post and suggesting some useful improvements.